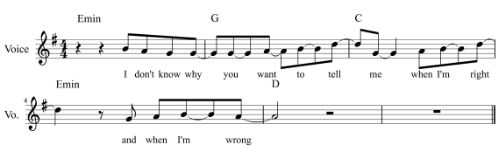

This song starts out moving back and forth between G minor and C minor chords for one measure each. The organ riff repeated (with variations) over these two chords very much feels like it resolves on the note C played over the C minor chord, so you have a strange situation where C minor is felt to be the key center but you're hearing the tonic chord in rhythmically weak bars (i.e., you don't hear the tonic in the first and third bars, but the second and fourth instead).

When they get to the end of the first verse, however, they play D as a dominant chord and resolve it to G minor (with the vocal melody resolving on G as well). Given that it's the end of the verse, this is a rest moment and organist Daryl Hooper momentarily leaves off on repeating the organ riff, picking it up again

half way through when the chord change starts again and they move to C minor one measure later. Starting the riff here, in the middle, is a bit of acknowledgment that C minor is the key center for the verse (which is starting again), but there's this beautiful awkwardness to the fact that it begins in the middle and in a rhythmically weak bar.

In my experience, the tonality I'm describing here in the verse is a very unique situation. The key center is not really, technically, ambiguous; it's C minor, but they play on the fact that it's G minor that you're hearing in the rhythmically strong bars by resolving it there at the end.

The other unique feature of the verse is that the vocal melody takes up the melodic emphasis on Eb as an emphasized upper neighbor tone heard over the G minor chord. Every line of the verse starts on the G minor chord (strong bar) and ends on the C minor chord (weak bar), and every line starts on that non-chordal tone of Eb. This is done so casually, and so comfortably, that it honestly sounds a little like

sprechstimme and the extremely clever harmonic aspect of what's going on here is easily glossed over.

Note: This entry refers to the wedding-themed version of this song, not the one labeled as "Reprise."